Cokerie-lavoir du Chanois

| Cokerie-lavoir du Chanois | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Built | 1898 |

| Location | Magny-Danigon, Haute-Saône, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France |

| Coordinates | 47°41′30″N 6°37′28″E / 47.691649°N 6.624547°E |

| Industry | Coke (fuel) |

The cokerie-lavoir du Chanois is an industrial complex of the Ronchamp collieries that combines coal sorting-screening, washing, and preparation:[1] facilities on a site adjacent to the Chanois pit, in Magny-Danigon, Haute-Saône, in the French region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté.[2][3]

The sorting-washing-screening workshops were built in 1898, replacing the small workshops at the Magny shaft.[4][5] A coal preparation plant was constructed between 1900 and 1920 to replace the furnaces in the Saint-Joseph shaft.[6] It closed in 1933, while the rest of the facilities remained in operation until the mines closed in 1958.[7]

Remnants of these installations remain from the early 21st century, including a reinforced concrete hopper.[8]

Location[edit]

The complex is located in Magny-Danigon, on the outskirts of Ronchamp, in the Haute-Saône department of the Burgundy-Franche-Comté region of France.[9] It lies on the Chanois plain, crossed by the Beuveroux and Rahin rivers. Its position forms a triangle with the Chanois well and the Ronchamp thermal power station, both 200 meters away.[10][11][12]

Sorting, screening and washing[edit]

In 1888, the Magny shaft was connected to the Chanois center by a railroad line extended in 1900 towards the Arthur-de-Buyer shaft, which was now in operation.[14]

The central workshops were set up near the Chanois coal mine in 1898,[15] enabling all the coal mined in Ronchamp to be processed via a rail network between the shafts. Wagons dump the coal into the upper part of the workshop.[16] It is then sifted and separated into two categories: the smallest fragments are sent to the coal preparation by conveyor belts, while the largest pieces are sorted by hand by women for direct shipment to customers. On the other hand, if it is not sufficiently free of sterile material, it is crushed to form flakes measuring less than seven centimeters before being sent to the coal preparation.[17][18]

- The large screening-washing building.

The Chanois washery is a Baum-type coal washery capable of processing 50 to 60 tons of coal per hour.[19][20] After treatment, the coal yields several different products[21]

- coke fines, which are drained and stored in a silo;

- flakes, which vary in size from 15 to 60 mm;

- mixed washes, which have to be treated again as they still contain coal;

- shale, which is evacuated to slag heaps;

- schlamms, the residual sludge obtained after washing.[19]

- The different products from the washing and screening process.

-

From left to right: 0-8 mm (washed menue), 8-12 mm (grains), 12-25 mm (grains), 25-40 mm (walnuts), 40-55 mm (walnuts), >55 mm (screened flakes).

The Coal preparation plant [edit]

A first series of furnaces were built before 1900.[22]

-

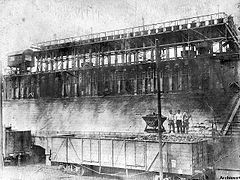

Furnace construction.

-

Cooling the glowing coke.

-

The coking plant in its early days.

In 1913, construction began on a battery of 28 horizontal coke ovens near the sorting and washing plant. Work was delayed by the First World War, and the plant was not commissioned until 1920.[19][23]

The Coal preparation plant produces over 130 tonnes of coke per day from 175 tonnes of greasy coal. The incandescent coke is dumped onto an inclined plane, where it is cooled by water jets before being discharged into railcars. The distillation of the coal yields benzol, ammonium sulfate (for agricultural use, in special workshops),[24] tar and distillate gas used to heat the furnaces.[19] The Coal preparation plant closed in 1933.[24]

-

The coking plant at its peak.

-

General view above the coking plant.

-

Coke ovens and the inclined plane.

-

The ruined coking plant.

Remains[edit]

In 2013, the Coal preparation plant and some small neighboring buildings are in ruins and overgrown.[25] One of the two hoppers is still standing,[26] while the second was dynamited by the army in the 1960s and left in place.[27] The Coal preparation plant's ancillary buildings, notably the benzol vats, are in ruins, except for one part which had been converted into a dwelling and still has a roof in good condition.[28] By contrast, the large wash-house and other buildings from the same period have been demolished without trace.[28] The remains of the Coal preparation plant were cleared in early 2015.[29]

-

General view of the facilities in 2015.

-

The old by-products building on the south side.

-

The concrete hopper still standing.

-

The other hopper collapsed.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Griffith, Edward D.; Clarke, Alan W. (1979). "World Coal Production". Scientific American. 240 (1): 38–47. Bibcode:1979SciAm.240a..38G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0179-38. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24965066.

- ^ "Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ "Cokerie-Lavoir du Chanois (documents d'époque) - 2 - Cartorum". cartorum.fr. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Bulletin de la Société géologique de France (in French). La Société. 1897.

- ^ Meunier, Stanislas (1889). Géologie régionale de la France: Cours professé au Muséum d'histoire naturelle (in French). Vve.C. Dunod.

- ^ "Les dossiers de la houillère de Ronchamp. 5. Le puits du Magny". Patrimoine en Bourgogne-Franche-Comté (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Hall, Clarence; Lyon, Dorsey Alfred; Clark, Harold Hayward; Darton, Nelson Horatio; Moore, Richard Bishop; Kithil, Karl Ludwig; Crocker, Ralph W.; Keeney, Robert Mayro; Howell, Spencer Pritchard (1913). Coal-mine Accidents in the United States and Foreign Countries. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ "Ronchamp. Les Amis du Musée de la Mine tiennent conférence". www.estrepublicain.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ France (1898). Journal officiel de la République française (in French).

- ^ "Bassin houiller de Ronchamp, by E. Trautmann | The Online Books Page". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Mines, United States Bureau of (1915). Bulletin. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Annales des mines (in French). Carilian-Goeury et V. Dalmont. 1860.

- ^ minérale (France), Société de l'industrie (1881). Bulletin trimestriel (in French).

- ^ Journal. 1901.

- ^ Burat, Amédée (1871). Cours d'exploitation des mines: Atlas (in French). Baudry.

- ^ Revue des deux mondes (in French). Au Bureau de la Revue des deux mondes. 1893.

- ^ Callon, Jules Pierre (1881). Lectures on Mining Delivered at the School of Mines, Paris. Dunod.

- ^ Trautmann, E. (1885). Bassin houiller de Ronchamp (in French). A. Quantin.

- ^ a b c d "Les ateliers dans la plaine du Chanois". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ France, Comité central des Houillières de (1909). Rapports des ingénieurs des mines aux conseils généraux sur la situation des mines et usines en 1908 (in French). Laguerre.

- ^ NiNa.Az. "Coke (charbon)". www.wikidata.fr-fr.nina.az (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Laur, Francis (1901). Les mines & la métallurgie à l'exposition Universelle de 1900 (in French). Société des Publications Scientifiques & Industrielles.

- ^ Trautmann, E. (1885). Bassin houiller de Ronchamp (in French). A. Quantin.

- ^ a b "Les vestiges des ateliers en images". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ "Les vestiges des fours à coke". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "La trémie d'alimentation du charbon". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "La trémie dynamitée vers 1960". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ a b "Bâtiment des fours à coke". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 4)

Bibliography[edit]

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2001). Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. I: La mine. Éditions Comtoises. ISBN 2-914425-08-2.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2010). Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. II: Les mineurs. Noidans-lès-Vesoul, fc culture & patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1.